Japanese Directors 101

This will be an on-going series where I hope to introduce newcomers to the amazing, eclectic world of Japanese cinema. Obviously to those who have been watching Japanese films for a while many names will be well known, but I hope there will be some new treats to investigate for everyone.

I came late to Japanese film. Like many other people, my viewing was limited to a handful of Kurosawa’s Samurai films and the J-Horror releases of the early 2000s. It was only shortly before my first visit to Japan in 2015 that I had started to watch the likes of Ozu and Suzuki Seijun, and most of Japanese production, both older and modern, was unknown to me. Since then I have been educating myself by watching some 500 Japanese films, jumping randomly around styles, genres and time periods. It’s been a fantastic journey of discovery.

PART 1: Japan encounters the world

When Japan began to open to the outside world with the coming of Commadore Perry’s black ships in 1853 there was a huge surge of interest in this hitherto barely known culture. In London, from whence I have moved to Tokyo, Japanese gardens were created in Kew and Holland Park, designers like Dresser and Godwin took inspiration from Japan in their architecture and furniture, and Japanese artworks were imported to every wealthy household.

In 1951 something similar happened when Kurosawa Akira’s film ‘Rashomon’ debuted at the Venice Film Festival. To the bafflement of Japanese critics, it was praised in the West, winning the Golden Lion at Venice and going on to be awarded an Honorary Oscar for best foreign language release in 1952. Japanese film suddenly became a commodity in the west. Honorary Oscars followed for Kinugasa Teinosuke’s ‘Gate Of Hell’ in 1954 and Inagaki Hiroshi’s ‘Samurai, The Legend of Musashi’ in 1955, while filmmakers like Mizoguchi Kenji and Ozu Yasujiro, already well known and respected in Japan, began to have there works released in the outside world.

Much like the centuries of culture behind the Japanese vogue of Victorian England, Japan had in fact been producing films since as early as 1897, followed presentations by the Lumiere Brothers, but now Japanese film became a major, unique, force in film both influencing and being influenced by the rest of the world.

Here I will be dealing with ‘The Three Masters’ who spearheaded this force.

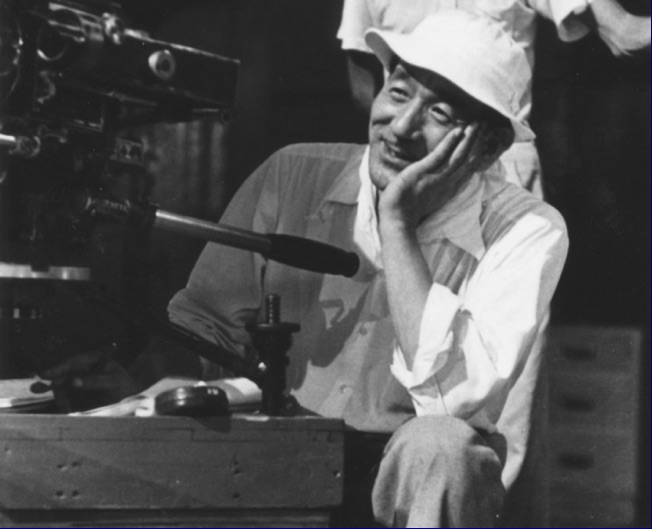

Kurosawa Akira

If someone has only heard of one Japanese director it will be Kurosawa. Recently I discovered he went to an elementary school just a few blocks from the ELFS Japan studio, so I am feeling a little bond! Kurosawa’s father encouraged Western ideas, and especially film, and his elder brother became a ‘benshi’, a narrator for silent films. Having aimed to be a painter it was perhaps his brother’s suicide in 1933 that pulled the young Akira towards the cinema himself.

In 1935 he began the usual path as an Assistant Director, even unofficially directing one film, 1941’s ‘Uma’, until he came to direct his first feature, the swordplay film ‘Sanshiro Sugata’, in 1943. This was from his own screenplay, and he came to the belief early that directors needed to learn to write their scripts. He also had a very western style, which brought censorship and opprobrium during the war years, and Capra, Griffith and, particularly, John Ford, were great influences on him.

It was after the war that Kurosawa began to find his voice and it was without his knowledge that ‘Rashomon’ was entered into the Venice Film Festival in 1951. From that point on Kurosawa became the face of Japanese cinema. Two films previously he had first worked with a young actor named Mifune Toshiro who went on to appear in 15 of Kurosawa’s 30 films, and created another international icon of Japanese film. His career, especially after a parting with Mifune in 1965, had many ups and downs, but by his death in 1998 he had maintained his position as the Japanese film director.

Essentially viewing: My first Kurosawa was ‘The Seven Samurai’, as it was for many, and you can’t go wrong with it. Having been influenced by John Ford and the Western genre things came full circle when it was adapted by Hollywood as ‘The Magnificent Seven’. Another samurai classic, ‘Yojimbo’ was unofficially adapted by Sergio Leone as ‘A Fistful of Dollars’. On viewing the film Kurosawa sent Leone a letter stating, ‘It is a very fine film, but it is my film’ and successfully sued for a share of proceeds.

My Choice: With my love of swordplay people may be surprised to know that my favourite Kurosawa is ‘Ikiru’, the story of a lowly civil servant who realises that his life has been a work of blocking people’s dreams, and learning of his own mortality he decides to push one project throught the system. It is a beautifully shot and acted film with an extraordinary central performance by Shimura Takashi, better known as the leader of the Seven Samurai.

Ozu Yasujiro

When Kurosawa won at Venice Japanese critics were horrified. Their choice for a true reprentative of Japanese cinema was Ozu, and it was only in Kurosawa’s wake that the older man’s films became known to the outside world.

Unlike Kurosawa, Ozu was not encouraged to watch films, but he played truant from school to do so and, again unlike Kurosawa, he decided early on to be a film director. It was against his father’s wishes that he joined the Shochiku studio in 1923, not as an assistant director, but in the cinematography department. However a mix of persistence and luck lead him to the director’s chair at an early age in 1927.

Ozu directed 34 silent films of which 19 are lost. Starting in student comedies and gangster movies he began to make an impression with social commentary. He maintained production of silent films as late as 1936, and as he did not take on colour until his final six films in 1958, it seems that Ozu was not prepared to take on new processes until he felt they had been perfected.

Like Kurosawa Ozu wrote his own scripts, except for a few early ones, generally collaborating with Noda Kogo, who measured progress on the scripts by the numbers of sake bottles consumed. Again like Kurosawa he formed a working relationship with an actor, this time leading lady Hara Setsuko, who leant a resigned beauty to six of his later films. When Ozu died in 1963 she retired, living in seclusion in Kamakura until 2015.

As the Japanese critics had opined Ozu brought aspects of Japanese character and culture to the screen, but it is in his shooting style that he stands apart from the westernised directors. His camera barely moves, and ceases to do so all together in his final colour films. Transitions come via close-ups of objects,characters face square to the camera rather than the usual ‘over the shoulder’ shot and much direction is ‘in depth’ through various doorways and windows in the background of shots. Most famous is his ‘tatami shot’, with the camera at the level of a person kneeling on a tatami.

Essential Viewing: ‘Tokyo Story’ has consistently, and deservedly, been listed in ‘best of’ polls for decades, sometimes toppling ‘Citizen Kane’ from the top spot. The story of an elderly couple visiting uncaring children in the big city, there is something of the King Lear about it (also adapted by Kurosawa as ‘Ran’). Hara Setsuko plays the widowed daughter-in-law who shows them the only kindness.

My Choice: Difficult to go beyond ‘Tokyo Story’, as that was my first and defining Ozu, but as a lover of silent film I will point you towards ‘I Was Born, But…’ from 1932, the story of two young brothers who lose faith in their father. Charming and funny, with great child performances, it rings true to many memories of our own childhoods.

Mizoguchi Kenji

The eldest of the three directors we’re looking at here, Mizoguchi’s film career began as an actor, but only after stints in theatre decoration and advertising. After three years as an actor he stepped behind the camera to direct and there followed 99 feature films, a full 65 of which are lost silents and early talkies.

Mizoguchi soon began to gain a reputation as a director of social commentary, particularly concerning the lowly role of women in Japanese society. While Kurosawa represented the new Western-influenced cinema, and Ozu was championed as the true Japanese visionary, by the time Japanese cinema had broken into the world consciousness Mizoguchi was already considered old-fashioned in Japan. However the new Western audience championed him and he produced his best known works towards the end of his life.

Mizoguchi is most famous for his long takes (“one-scene-one-shot”) and for his focus on female protagonists. His sister had been sold into geishahood at an early age and it is hard not to see this influencing his work, such as ‘Sisters of the Gion’ set in Kyoto’s geisha quarter. It is unsurprising, therefore, that his best known working relationship was with actress Tanaka Kinuyo, who stared in 15 of his films. However his support was limited as he was vehemently against her decision to direct herself in 1953, when her film ‘Love Letter’ made her only the second Japanese woman to direct a movie.

Mizoguchi’s fascinating private life has sometimes overshadowed his work, and was the subject of Shindo Kaneto’s brilliant documentary ‘Kenji Mizoguchi: The Life of a Film Director’.

Essential Viewing: 1953’s ‘Ugetsu’ is generally considered Mizoguchi’s masterpiece and followed ‘Rashomon’ by winning the silver lion at Venice. A period ghost story it tangentially challenges the attitudes that lead to Japan’s wars earlier in the century, and in particular their effect on women. The cinematography is truly breathtaking.

My Choice: ‘The Life of Oharu’ deals with the decline of it’s protagonist (played by Tanaka) from the daughter of a wealthy family to courtesan, servant, nun and prostitute. Beautiful shot and paced, and with an extraordinary central performance, it challenges the status of women in the society of the time, but also makes us aware that not that much has changed.

Next Time: I’ll be looking into some lesser known names of early Japanese cinema before launching into the modern world! See you then.

About Rory O’Donnell

Rory O’Donnell worked in the UK entertainment industry for 25 years, initially as an actor, then a casting director, before spending ten years as course director for Raindance London, the UK’s top provider of short training courses for filmmakers. He is an award-winning filmmaker, with short films he has directed screening in festivals in Europe and North America. His students have included everyone from film professionals looking to broaden their skillsets to inexperienced novices with a passing interest in the subject. Building on this experience, he has developed classes accommodating to all backgrounds and abilities.

Ready to learn filmmaking?

Join our Making the Short Film masterclass

Begins August 13